One of the things Ben and I have been discussing a lot is the concept of the One Metric That Matters (OMTM) and how to focus on it.

One of the things Ben and I have been discussing a lot is the concept of the One Metric That Matters (OMTM) and how to focus on it.

Founders are magpies, chasing the shiniest new thing they see. Many of us use a pivot as an enabler for chronic ADD, rather than as a way to iterate through ideas in a methodical fashion.

That means it’s better to run the risk of over-focusing (and miss some secondary metric) than it is to throw metrics at the wall and hope one sticks (the latter is what Avinash Kaushik calls Data Puking.)

That doesn’t mean there’s only one metric you care about from the day you wake up with an idea to the day you sell your company. It does, however, mean that at any given time, there’s one metric you should care about above all else. Communicating this focus to your employees, investors, and even the media will really help you concentrate your efforts.

There are three criteria you can use to help choose your OMTM: the business you’re in; the stage of your startup’s growth; and your audience. There are also some rules for what makes a good metric in general.

First: what business are you in?

We’ve found there are a few, big business model Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) that companies track, and they’re dictated largely by the main goal of the company. For online businesses, most of them are transactional, collaborative, SaaS-based, media, game, or app-centric. I’ll explain.

Transactional

Someone buys something in return for something.

Transactional sites are about shopping cart conversion, cart size, and abandonment. This is the typical transaction funnel that anyone who’s used web analytics is familiar with. To be useful today, however, it should be a long funnel that includes sources, email metrics, and social media impact. Companies like Kissmetrics and Mixpanel are championing this plenty these days.

Collaborative

Someone votes, comments, or creates content for you.

Collaboration is about the amount of good content versus bad, and the percent of users that are lurkers versus creators. This is an engagement funnel, and we think it should look something like Charlene Li’s engagement pyramid.

Collaboration varies wildly by site. Consider two companies at opposite ends of the spectrum. Reddit probably has a very high percentage of users who log in: it’s required to upvote posts, and the login process doesn’t demand an email confirmation look, so anonymous accounts are permitted. On the other hand, an adult site likely has a low rate of sign-ins; the content is extremely personal, and nobody wants to share their email details with a site they may not trust.

On Reddit, there are several tiers of engagement: lurking, voting, commenting, submitting links, and creating subreddits. Each of these represents a degree of collaboration by a user, and each segment represents a different lifetime customer value. The key for the site is to move as many people into the more lucrative tiers as possible.

SaaS

Someone uses your system, and their productivity means they don’t churn or cancel their subscription.

SaaS is about time-to-complete-a-task, SLA, and recency of use; and maybe uptime and SLA refunds. Companies like Totango (which predicts churn and upsell for SaaS), as well as uptime transparency sites like Salesforce’s trust.salesforce.com, are examples of this. There are good studies that show a strong correlation between site performance and conversion rates, so startups ignore this stuff at their peril.

Media

Someone clicks on a banner, pay-per-click ad, or affiliate link.

Media is about time on page, pages per visit, and clickthrough rates. That might sound pretty standard, but the variety of revenue models can complicate things. For example, Pinterest’s affiliate URL rewriting model, which requires that the site take into account the likelihood someone will actually buy a thing as well as the percentage of clickthroughs (see also this WSJ piece on the subject.)

Game

Players pay for additional content, time savings, extra lives, in-game currencies, and so on.

Game startups care about Average Revenue Per User Per Month and Lifetime Average Revenue Per User (ARPUs). Companies like Flurry do a lot of work in this space, and many application developers roll their own code to suit the way their games are used.

Game developers walk a fine line between compelling content, and in-game purchases that bring in money. They need to solicit payments without spoiling gameplay, keeping users coming back while still extracting a pound of flesh each month.

App

Users buy and install your software on their device.

App is about number of users, percentage that have loaded the most recent version, uninstalls, sideloading-versus-appstore, ratings and reviews. Ben and I saw a lot of this with High Score House and Localmind while they were in Year One Labs. While similar to SaaS, there are enough differences that it deserves its own category.

App marketing is also fraught with grey-market promotional tools. A large number of downloads makes an application more prominent in the App Store. Because of this, some companies run campaigns to artificially inflate download numbers using mercenaries. This gets the application some visibility, which in turn gives them legitimate users.

It’s not that simple

No company belongs in just one bucket. A game developer cares about the “app” KPI when getting users, and the “game” or “SaaS” KPI when keeping them; Amazon cares about “transactional” KPIs when converting buyers, but also “collaboration” KPIs when collecting reviews.

There are also some “blocking and tackling” metrics that are basic for all companies (and many of which are captured in lists like Dave McClure’s Pirate Metrics.)

- Viral coefficient (how well your users become your marketers.)

- Traffic sources and campaign effectiveness (the SEO stuff, measuring how well you get attention.)

- Signup rates (how often you get permission to contact people; and the related bounce rate, opt-out rate, and list churn.)

- Engagement (how long since users last used the product) and churn (how fast does someone go away). Peter Yared did a great job explaining this in a recent post on “Little Data”

- Infrastructure KPIs (cost of running the site; uptime; etc.) This is important because it has a big impact on conversion rates.

Second: what stage are you at?

A second way to split up the OMTM is to consider the stage that your startup is at.

Attention, please

Right away you need attention generation to get people to sign up for your mailing list, MVP, or whatever. This is usually a “long funnel” that tracks which proponents, campaigns, and media drive traffic to you; and which of those are best for your goals (mailing list enrollment, for example.)

We did quite a lot of this when we launched the book a few weeks ago using Bit.ly, Google Analytics, and Google’s URL shortener. We wrote about it here: Behind the scenes of a book launch

Spoiler alert: for us, at least, Twitter beats pretty much everything else.

What do you need?

Then there’s need discovery. This is much more qualitative, but things like survey completions, which fields aren’t being answered, top answers, and so on; as well as which messages generate more interest/discussion are quantitative metrics to track. For many startups, this will be things like “how many qualitative surveys did I do this week?”

On a slightly different tone, there’s also the number of matching hits for a particular topic or term—for example, LinkedIn results for lawyers within 15km of Montreal—which can tell you how big your reachable audience is for interviews.

Am I satisfying that need?

There’s MVP validation—have we identified a product or service that satisfies a need. Here, metrics like amplification (how much does someone tell their friends about it?) and Net Promoter Score (would you tell your friends) and Sean Ellis’ One Question That Matters (from Survey.io—”How would you feel if you could no longer use this product or service?“) are useful.

Increasingly, companies like Indiegogo and Kickstarter are ways to launch, get funding, and test an idea all at the same time, and we’ll be looking at what works there in the book. Meanwhile, Ben found this excellent piece on Kickstarter stats. We’re also talking with the guys behind Pen Type A about their experiences (and I have a shiny new pen from them sitting on the table; it’s wonderful.)

Am I building the right things?

Then there’s Feature optimization. As we figure out what to build, we need to look at things like how much a new feature is being used, and whether the addition of the feature to a particular cohort or segment changes something like signup rates, time on site, etc.

This is an experimentation metric—obviously, the business KPI is still the most important one—but the OMTM is the result of the test you’re running.

Is my business model right?

There’s business model optimization. When we change an aspect of the service (charging by month rather than by transaction, for example) what does that do to our essential KPIs? This is about whether you can grow, or hire, or whether you’re getting the organic growth you expected.

Later, many of these KPIs become accounting inputs—stuff like sales, margins, and so on. Lean tends not to touch on these things, but they’re important for bigger, more established organizations who have found their product/market fit, and for intrapreneurs trying to convince more risk-averse stakeholders within their organization.

Third: who is your audience?

A third way to think about your OMTM is to consider the person you’re measuring it for. You want to tailor your message to your audience. Some things you share internally won’t help you in a board meeting; some metrics the media will talk about are just vanity content that won’t help you grow the business or find product/market fit.

For a startup, audiences may include:

- Internal business groups, trying to decide on a pivot or a business model

- Developers, prioritizing features and making experimental validation part of the “Lean QA” process

- Marketers optimizing campaigns to generate traffic and leads

- Investors, when we’re trying to raise money

- Media, for things like infographics and blog posts (like what Massive Damage did.)

What makes a good metric?

Let’s say you’ve thought about your business model, the stage you’re at, and your audience. You’re still not done: you need to make sure it’s a good metric. Here are some rules of thumb for what makes a number that will produce the changes you’re looking for.

- A rate or a ratio rather than an absolute or cumulative value. New users per day is better than total users.

- Comparative to other time periods, sites, or segments. Increased conversion from last week is better than “2% conversion.”

- No more complicated than a golf handicap. Otherwise people won’t remember and discuss it.

- For “accounting” metrics you use to report the business to the board, investors, and the media, something which, when entered into your spreadsheet, makes your predictions more accurate.

- For “experimental” metrics you use to optimize the product, pricing, or market, choose something which, based on the answer, will significantly change your behaviour. Better yet, agree on what that change will be before you collect the data.

The squeeze toy

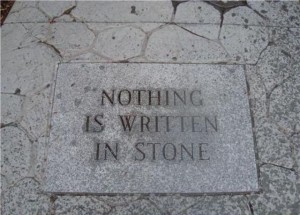

There’s another important aspect to the OMTM. And I can’t really explain it better than with a squeeze toy.

Nope, this isn’t me. But sometimes I feel like this.

If you optimize your business to maximize one metric, something important happens. Just like one of the bulging stress-relief toys shown above, squeezing it in one place makes it bulge out in others. And that’s a good thing.

A smart CEO I worked with once asked me, “Alistair, what’s the most important metric in the business right now?”

I tried to answer him with something glib and erudite. He just smiled knowingly.

“The one that’s most broken.”

He was right, of course. That’s what focusing on the OMTM does. It squeezes that metric, so you get the most out of it. But it also reveals the next place you need to focus your efforts, which often happens at an inflection point for your business:

- Perhaps you’ve optimized the number of enrolments in your gym—but now you need to focus on cost per customer so you turn a profit.

- Maybe you’ve increased traffic to your site—but now you need to maximize conversion.

- Perhaps you have the foot traffic in your coffee shop you’ve always wanted—but now you need to get people to buy several coffees rather than just stealing your wifi for hours.*

Whatever your current OMTM, expect it to change. And expect that change to reveal the next piece of data you need to build a better business faster.

(* with apologies to the excellent Café Baobab in Montreal, where I’m doing exactly that.)