The Lean Hair Salon

Yesterday, I had an interesting conversation with, of all people, my hairdresser. Those who know me realize there isn’t much hair to dress, so it was an unusual event to begin with. As it turns out, she’s just bought a one-person barbershop and this was her last week at her current employer’s shop.

Yesterday, I had an interesting conversation with, of all people, my hairdresser. Those who know me realize there isn’t much hair to dress, so it was an unusual event to begin with. As it turns out, she’s just bought a one-person barbershop and this was her last week at her current employer’s shop.

In hushed tones, under the sound of scissors, she told me about her marketing plans: “I just got my business cards printed and I’m making a Facebook page. I don’t get Twitter.”

I gave her a few ideas:

- Encourage people to post pictures of the cuts they liked to her page, where others can Like them, and each month give one person who does so a cut for free

- Go see all the concierges of hotels in the area and ask them to come for a free cut, so they recommend it to visitors

- Canvas movers on July 1 with a campaign since they just moved to the area (July 1 is moving day in Quebec.*)

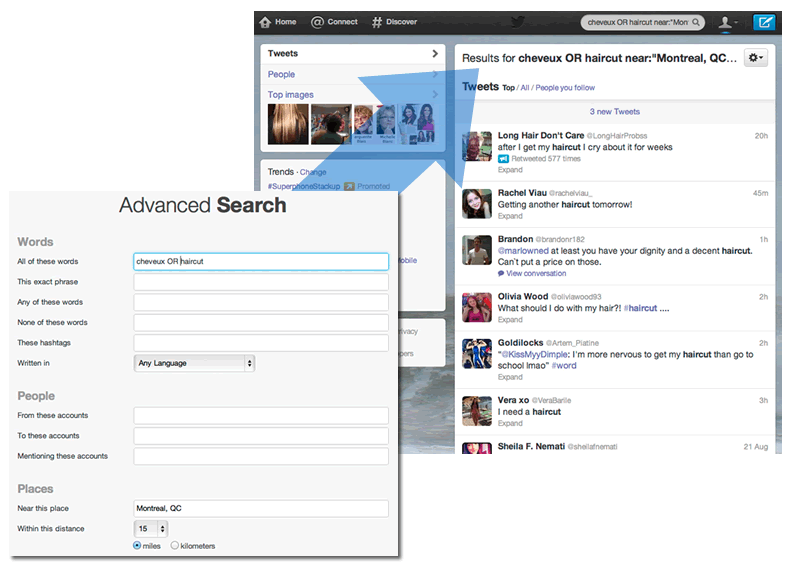

- Set up a Twitter search for “haircut” with a region of “Montreal” and respond to people when they mention it, and offer them a code by DM

She asked me how I was coming up with all these ideas. And I tried to explain to her (in halting French), “well, I’m thinking about what makes someone change salons. Their friend gets a good cut; they’re visiting from out of town; they just moved. And that’s the moment when you can change their minds.”

She replied, “these are great! I’m going to do them!”

I asked her, “all of them? but why?”

“Because they’re free!” she answered. “Even printing my business cards cost more than some of these.”

I agreed with her: “This is the change that businesses have undergone in the past decade. The price of marketing has gone down to almost zero, if you can just find a way to be in the right place at the right time with the right message. But most small businesses still think about marketing as fliers, a Yellow Pages ad, and some business cards.”

“So I should do all of them, right?” she asked excitedly.

And I shot her down. “No,” I said, “you’re going to try them. You need to measure whether they work. Better yet, go home, grab a few beers and a pad and paper, and figure out all the ways that someone finds out about you and decides to try you. Then, for each of those, figure out ways that you might join that conversation in a way that doesn’t suck.”

She paused for a while, forgetting to cut what’s left of my hair, and I could almost see the wheels turning.

Once she came out of her daze I said, “and then figure out how to measure it. You have a barber shop to staff—you’re the only employee. You need to kill the bad ideas fast, and find someone else—preferably a piece of software or a friend—to do the good ideas repeatedly. You’re not a hairstylist any more, you’re an entrepreneur, because you bought your own business.”

She was clearly starting to get it—although she was probably also reconsidering her decision to strike out on her own.

So I said, “this is the difference between an employee and an entrepreneur. You’re not in search of the perfect haircut, you’re in search of a sustainable way to grow your business and bring in revenue.”

It occurred to me at this point that most small business owners define themselves by the work they do within the business (cutting hair, mowing a lawn, driving a truck, running a lemonade stand) and not by the customer need they’re addressing (a neat appearance that gets them promoted, a lawn that complies with town by-laws, relocation, learning about business.)

A worker becomes an entrepreneur when they re-frame themselves. They’re no longer the cog in the machine—they’re the architect of the machine. The watchmaker, not the watch. And that means they start asking what the machine is for, how it can be improved, what else it can do, and which other machines satisfy the need.

“In the end, it may even be that your customers don’t want haircuts, they want something else—fashion consulting, pedicures, personal training, someone to talk to. Or maybe you should be a travelling stylist who does work on demand for hotels. How would you find out about that and figure out what other needs customers have that you can help with? And how could you use those to become unique, or more efficient, or more profitable?”

The conversation reminded me that lean principles apply to everything, and are increasingly relevant to small businesses. Today’s one-person company has tools at its disposal that the Fortune 500 only dreamed of a decade ago. Entrepreneurs can make data-driven decisions, run experiments, segment customers, and iterate.

They just need to stop thinking of themselves as part of the machine, and start seeing themselves as its designer.

* 4% of the population moves on that day. No, there aren’t any trucks available. Go ahead, mock us.

Follow

Follow

Leave a Reply