Lean Analytics for Intrapreneurs

Later today, I’ll be speaking at the Lean Startup conference in San Francisco. It seems like only yesterday that Ben and I first taught a workshop on Lean Analytics, prior to the book’s launch. Since that time, we’ve visited a dozen countries, spoken with hundreds of founders, and found out that it’s being translated into eight languages. To say we were surprised by the progress is an understatement.

Rather than repeat last year’s content—which is widely available on Slideshare, on Udemy, and in classrooms by now—Ben and I have spent the past six months talking to Intrapreneurs. These are people within larger organizations, trying to create innovation. It’s a hard, often thankless job. After all, if a startup is an organization designed to search for a sustainable, repeatable business model, then a corporation is designed to perpetuate a business model. And in environments of rapid change and high uncertainty, perpetuating business models is deadly.

The most fundamental truth of intrapreneurship is that the difference between a special operative and a rogue agent is permission.

If you’re trying to change things, but don’t have organizational backing, you can do it—but you have to be subversive, and pick your battles. You’re tilting at windmills, battling on a pitched field against large, slow, old-fashioned incumbents. On the other hand, if your organization has a deliberate portfolio of innovation, then you’re going to need a program to find, test, incubate, and integrate new ideas.

If you’re trying to change things, but don’t have organizational backing, you can do it—but you have to be subversive, and pick your battles. You’re tilting at windmills, battling on a pitched field against large, slow, old-fashioned incumbents. On the other hand, if your organization has a deliberate portfolio of innovation, then you’re going to need a program to find, test, incubate, and integrate new ideas.

Batch size changes everything

One of the biggest changes affecting companies of all shapes and sizes is the ability to do things in small batches. Once, scale mattered a lot, because it the only way to get the incremental cost of a customer down was to amortize fixed costs across many sales. This worked well, for a while, and gave us everything from mass production to broadcast media.

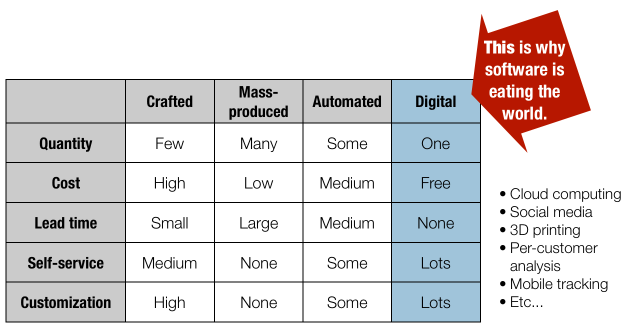

But that model is crumbling: tools like social media and on-demand printing and automation are reducing the economic order quantity. Part of this is because software is eating the world, optimizing the back-office and supplanting other channels as the dominant means of communication and delivery on the front end. Consider how quantity, cost, lead time, self-service, and customization vary across different production models.

Is it any wonder that we’re seeing most innovation in digital sectors?

Big companies are taking notice. We’ve spoken with around 30 large multinationals—GE, DHL, SCA, Motorola, Google, Time, VMWare, Metlife and so on—in the last six months. Each of them has a slightly different take on innovation:

- Some prefer to incubate new products in-house; others favor acquisition.

- Some source ideas through hackathons and crowdfunding; others work closely with early-adopter customers.

- Some believe innovators need isolation, in a kind of Skunk Works model; others want innovation to live within the business units that will ultimately reap the benefits of invention.

- All seem to differentiate between three kinds of innovation. Some use the Three Horizons model; others distinguish between core, adjacent, and transformational projects.

Despite these differences, they all agree on one thing: that innovation must happen, and that to survive, companies have to constantly reframe the business they’re in and disrupt themselves.

We’re myopic about how

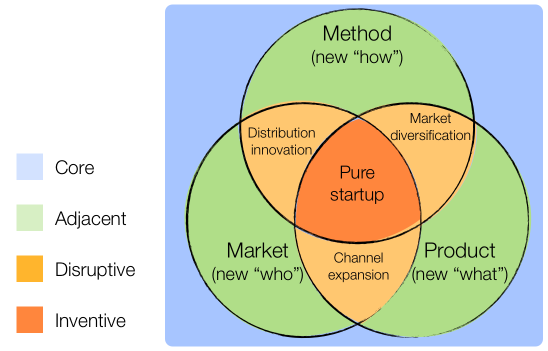

For us, the real lesson of the last six months’ research is that companies spend too much time worrying about adjacent markets (who they sell to) or adjacent products (what they sell them) while ignoring how they sell. It seems that while everyone knows about product/market fit, there’s a myopia around method.

Igor Ansoff’s product/market matrix is common wisdom for business strategists. We’re taught it in business school, and it’s the basis for most strategic discussions of diversification. And yet it’s only two-dimensional, focusing on product and market. There’s no method. It assumes the how. This is undoing of many incumbents. One of the things we’ll propose today is that intrapreneurship is about product/market/method iteration, and that innovation involves changing one (or more) of those three dimensions.

The more dimensions you’re changing, the less your metrics resemble typical business cases and the more they focus on de-risking your assumptions through validated learning.

I should point out that a marketing purist would argue that “product” includes the pricing, distribution, and promotion as well as the product itself, and therefore encompasses the “how.” I should know; I’m a marketing purist. But it’s worth breaking out how as a separate thing, because it’s far too often overlooked. Call it go-to-market strategy, or unfair advantage, or method—it’s still the thing people forget, and yet it’s the thing that drives most of the successful innovation we’ve seen.

Amazon, at its core, sold books to readers. Neither the market nor the product was new; it was the method (e-commerce, with recommendations and a focus on logistics) that was new. Later, they were able to diversify the product (kitchenware) and the market (people with poor eyesight who could read Kindle books with large typefaces.) Amazon gets this, which is why it experiments with cloud computing and drones.

Indeed, there may never have been a company as good at iterating on how as Amazon. This is the core reason why its stock price is high despite its score on traditional dimensions like profit and margin. Amazon is really good at cycle time, and while accountants don’t have a good way of measuring “how fast you learn and experiment”, capital markets do.

There’s no evidence about the future

When companies “assume the how,” they reinforce the processes, IP, and organizational structure that makes them really good at the way they work today. For decades, management theorists have urged us to grow and standardize, believing that tomorrow is the same as today, only more so. As a result, sustainable competitive advantage came from those who achieved scale and predictability.

But here’s the thing: there’s no evidence about the future.

Rita Gunther McGrath, author of The End of Competitive Advantage, says that sustainable competitive advantage allows for inertia and power to build up along the lines of an existing business model, which will soon die. Instead, she says, we should seek transient competitive advantage. And this is why Lean methods are so relevant to big, entrenched organizations.

Back to analytics

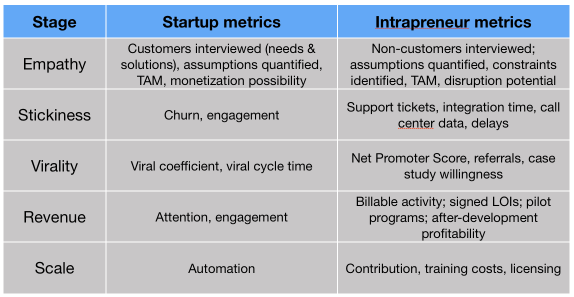

Our discussions with Intrapreneurs, CTOs, and managers of innovation labs have taken us far afield from the original scope of the book. We haven’t spent as much time talking about analytics, in part because what you measure depends on the change you’re trying to produce. In many markets—particularly those without direct customer instrumentation—intrapreneurs have to use proxy data to estimate things like virality, engagement, and conversion rate. This is hard, and full of errors.

There’s also a lack of comparative data across incubators and innovation programs, although this is gradually being addressed as companies formalize their programs and communicate among one another.

Today’s workshop will be our Minimum Viable Presentation. It’s the first time most of the 265 slides have seen the light of day, and I’m eager to see what works and what sucks so I can get to the next iteration.