Fast boat, fast river

Paul Graham has a simple definition of a startup: an organization designed to grow fast. Steve Blank adheres to a different one: an organization formed to search for a repeatable and scalable business model.

Paul Graham has a simple definition of a startup: an organization designed to grow fast. Steve Blank adheres to a different one: an organization formed to search for a repeatable and scalable business model.

They’re both right, in a way. And that has important implications for entrepreneurs

Many people think a startup is a small business. It’s not. A small business is a small business, and if you want to change that, you’ll have to follow both Paul and Steve’s advice: start searching for a sustainable business model that can grow fast.

Paul’s view

Let’s talk about Paul’s view first. He explains that while tech companies aren’t necessarily startups—Dell and Microsoft aren’t growing rapidly—startups might necessarily be tech companies. That’s because fast growth happens either from a big market shift, or from a dramatic lubrication of a market. Technology causes both huge shifts and copious amounts of lubrication.

- Tectonic changes in the market: Consider Google or Dropbox. They grew fast because of a huge, irresistible shift—the use of the web, or the willingness of the average person to store data in the cloud. There are plenty of other reasons they grew, but they were part of a rapidly expanding total addressable market. The market they targeted came out of nowhere, and grew very, very fast. If startups are boats on a river, then these ones are going fast because the river’s a rushing torrent.

- Reduction of friction in the market: Now consider Über or Groupon. There’s nothing necessarily disruptive about taxi services or coupon clipping. Those are slow rivers. But both companies found ways to lubricate the inherent friction in their markets: smartphone-equipped limos; or social sharing with a threshold incentive. These are the fast boats.

Put another way, startups move fast downriver, either because they’re on a really fast river, or because they have a motorboat and everyone else is in a canoe. Graham thinks (and I agree) that to achieve fast growth, most of the time you need a low-cost, short-cycle-time mechanism. And that’s usually software, because humans make bad processes. As Andreesen said, software eats everything. People retire; software gets upgraded.

Put another way, startups move fast downriver, either because they’re on a really fast river, or because they have a motorboat and everyone else is in a canoe. Graham thinks (and I agree) that to achieve fast growth, most of the time you need a low-cost, short-cycle-time mechanism. And that’s usually software, because humans make bad processes. As Andreesen said, software eats everything. People retire; software gets upgraded.

Steve’s view

Okay, on to the other definition. Startups are searching for a scalable and repeatable business model. To me, that means it’s sustainable without the direct involvement of the people who created it, because founders don’t scale.

A startup is not a lifestyle business. A startup does not mean consulting. It does not mean bespoke.

Etsy is sustainable; one-off quirky knitted sweaters are not. Etsy is software; sweaters are slow, messy, hard-to-scale wool. Sustainable, to me, means that as the business grows, the incremental cost of acquiring additional revenues or customers descends towards zero.

A few months ago, I wrote about a hairstylist who’s setting out on her own. She’s a small business owner. She can learn plenty from Lean methodologies about how to improve her business, just as Fortune 500 companies can improve their competitiveness by using Lean approaches. But she’s not a startup by either Steve or Paul’s definition.

A few months ago, I wrote about a hairstylist who’s setting out on her own. She’s a small business owner. She can learn plenty from Lean methodologies about how to improve her business, just as Fortune 500 companies can improve their competitiveness by using Lean approaches. But she’s not a startup by either Steve or Paul’s definition.

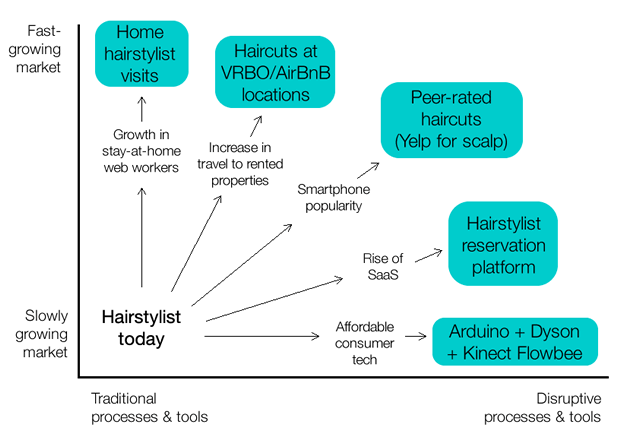

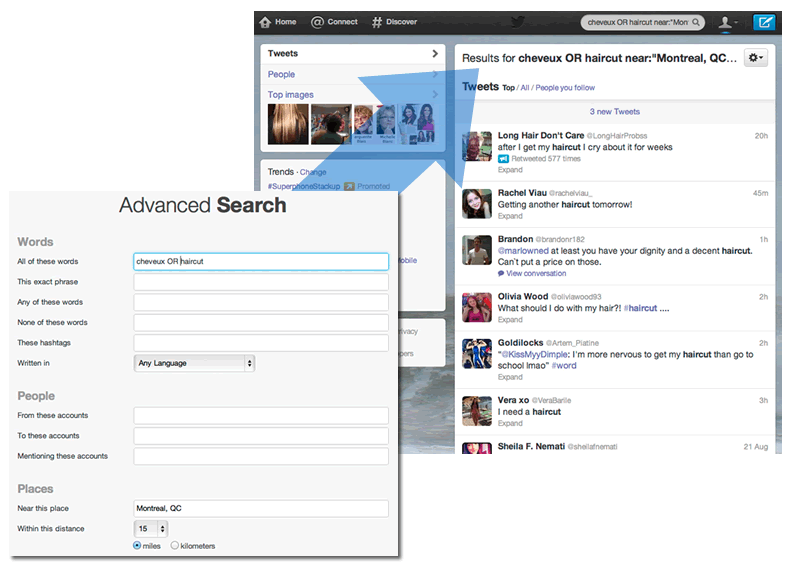

Since Paul mentioned a barber shop as an example of a not-startup, I wondered, “what would a hairstylist need to do to become a startup?” They’d have to be searching for a sustainable business model that could grow fast, probably because of a new market or a lubricant that changes the economics of an existing one in an important way.

Consider some of the ways a hairstylist might try to launch a startup, based on their domain expertise. They could focus on a market that they feel is growing quickly; or on a technology that makes new products possible.

Your source of growth drives your metrics

The source of your growth will influence the kinds of metrics you measure, and which you consider riskiest, and how much of your product or service needs to be built before you can test it. Some of these business models are SaaS; some are e-commerce; some are user-generated content. Each makes money in different ways: subscriptions; transactions; advertising. And all of that drives the One Metric That Matters for these companies.

Growing market (fast river)

If you choose to innovate by focusing on a growing market (fast river), then most of your risk is about whether you can capture that market. You’ll need a really good go-to-market strategy, because you’re not really doing anything new (you’re still cutting hair, just not in the traditional walk-in hair salon way.) You’ll care about exclusivity, partnerships, and existing competitors going after the same blue ocean.

Exclusivity means you’re the only one on the fast river. Partnerships mean that others already on the river help you get there. And competitors reduce your advantage, since they have the same fast waterway as you. The longer you can stay on a fast river, the better—but these days, it’s a fair bet that competitors will quickly copy you. Worse, several Internet giants (Google, Facebook, Twitter, etc.) are really, really good at fast rivers, since they run the underlying infrastructure. They shape the riverbed, and can divert the river’s course or slow the river to their advantage—think Twitter changing its APIs, or Facebook blocking an app’s access to its graph.

(It should be noted that neither home visits nor AirBnB haircuts are growing fast enough to qualify for Paul’s “designed for rapid growth.” That kind of growth takes something truly new, and often exploding because of network effects: the phone system, the Internet, credit cards, television, the printing press.)

Disruptive technology (fast boat)

If you choose to innovate by focusing on a disruptive technology (the fast boat in this analogy), you’re going to care more about whether you can build and run it; whether it will work and easily replace existing solutions; and whether it will really go as fast as you think it will.

The “can you build it?” question is true only of genuinely innovative technology, and often your adoption will come from patents or the barriers to entry that you create because of your invention. Your risk is that your Arduino/Dyson/Kinect Frankenscissors might not work.

Invention is a special segment of the startup world, and its value comes from an ability to demand high margins because of the advantage the product conveys to those who use you. For example, a chip manufacturer that increases network performance tenfold charges far more than the cost of making a chip, because of the value it conveys to network infrastructure that uses it.

The “will it work?” question is about substitution. If people won’t consider your offering a viable substitute, it’s no good. If Über cars weren’t widely available at launch, they wouldn’t be a viable alternative to taxis—which is why Über paid drivers $30 an hour to sit idle when they first launched. They basically rented a city’s population of limos until their demand took off. A good rule of thumb is that something must be ten times better than the alternative. Humans have intertia, and incumbents have inertia, and you need to overcome both.

The “speed” question is about being able to achieve the volume and cycle time you expect. Let’s say you think you can do a perfect haircut in 30 seconds because of your new hair-cutting invention, which will give you a 60-fold increase in productivity. You’re still running a salon. Your business hasn’t changed (much.) But there’s real risk that some other element of your business model (say, reservation management) becomes a bottleneck that prevents growth.

Both at once

If you’re doing both (new idea in a new market—fast boat on a fast river) you’ve got even more risk, because you have to focus on market fit and product fit. The best companies do this:

- Microsoft’s Windows was a motorboat, and the home PC was a fast river.

- Credit cards were a motorboat, and the rise of consumer banking was a fast river.

- Google’s Pagerank was a motorboat, and the rise of the consumer web was a fast river.

But it’s taken an amazing amount of dexterity for these companies to stay around, and they’ve had to adjust constantly. Microsoft nearly steered their motorboat into the shore when the Web happened, and it took a draconian intervention by Bill Gates to get them back on course. David Allen explains this history in his consequences of state interference and non-interference.

Coming upon this scene about two years ago, in late 1995, Bill Gates found that his Microsoft was caught flat-footed. The company’s cash flows were tied to desktop computing, but there was a fundamental shift underway, toward networked computing. Remarkably, among many such performances by the man, he turned his leviathan virtually “on a dime” and steamed it off in relentless and vigorous pursuit of the Internet.

In other words: Beware the founder claiming to have a fast boat on a fast river.

Startups aren’t easy

It should be obvious that I’m not suggesting anyone go launch Airbnb for haircuts and the other business models I’ve mentioned here. These are bad examples. That was precisely the point of Paul’s post:

…if you want to start a startup, you’re probably going to have to think of something fairly novel. A startup has to make something it can deliver to a large market, and ideas of that type are so valuable that all the obvious ones are already taken.

That space of ideas has been so thoroughly picked over that a startup generally has to work on something everyone else has overlooked.

The issue here isn’t that a hairstylist couldn’t launch a startup. It’s that the realm of hairstylist-related innovations is relatively small, and unlikely to yield something fast-growing in a big market. That’s why good ideas are scarce, and investors snap them up for what seem like unreasonable valuations. A speedboat on a fast river is a rare thing indeed, and they all want to get on board.

So consider this corollary: Invest in the founder who’s found a fast boat on a fast river, and whose idea seems daft at first and obvious in hindsight.

A conscious decision

Many entrepreneurs delude themselves into thinking they’re building startups, when in fact they’re building businesses. There’s nothing wrong with building businesses. In fact, it’s amazing. The hairstylist isn’t a startup founder, she’s a small business owner, and that’s fine. She has many of the same problems, but she isn’t girding herself for fast growth or searching for a sustainable, repeatable model.

What a lot of entrepreneurs who run lifestyle businesses don’t get is this: if they become a startup they’re quitting their job. They’re shutting down the current business (or finding someone to run it for them as a cash cow) and launching an entirely new one. None of the companies in my nonsense example above are a hairstylist—they’re a reservation platform, or a haircutting machine, or an iPhone app.

Until they mentally “quit” their lifestyle-oriented, slow-growth, unsustainable, unrepeatable jobs, they’ll never turn their businesses into startups. And that’s one reason why it’s so hard for small business owners to become startup founders.

They need to change jobs.