This is a really long post. It’s overly personal. It’s a bit of a travel triptych. But if you read through it, I hope you’ll find that there’s an important lesson in here for entrepreneurs.

I was in Austin for SXSW this year. It was my first time there—I’ve always had some other event to attend. I’ve been told it has long since jumped the shark, and many who’ve decried its demise say it’s proof that technology is mainstream. With that in mind, and not knowing anyone, I fully expected it to feel like crashing someone else’s high school reunion only to find that all the cool kids had already snuck out the back for a smoke.

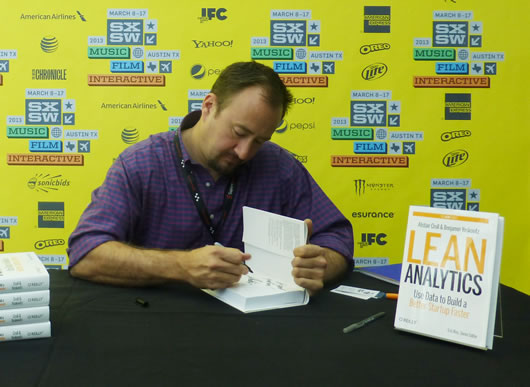

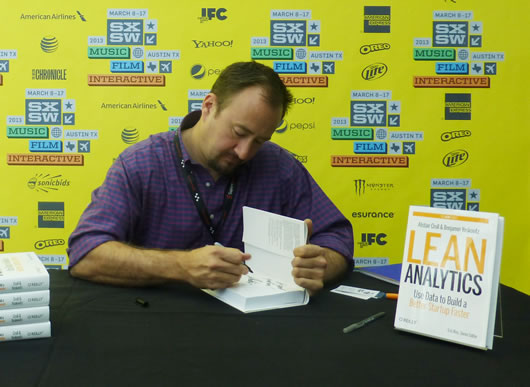

I was presenting a workshop on social media measurement, playing the part of the curmudgeonly entrepreneur; and I was there for the launch of the book, and as a mentor for Eric Ries’ Lean Startup event.

I also managed to squeeze in an interesting afternoon with librarians at a guerilla “salon” they’d erected just beyond the confines of downtown Austin. Turns out I knew people, too: Blake Robinson of Analect took me under his wing, and my colleagues from Decibel showed up towards the end, ushering me into a fantastic set by Flying Lotus. I also had a bumpy, sweaty ride around the city on an RV that felt (and smelled) like a moving version of Spring Break. It says a lot about the festival that this RV had just performed engagement ceremonies for the Twitterati.

But all of these paled in comparison to my experience with bikes.

I need to be less sedentary, and I’m trying to find hacks to do so, as I’ve outlined elsewhere. When I started planning for SXSW, the closest hotel I could find was five miles North of the city. Wary of waiting in interminable shuttle lines or spending a lot on cabs, I thought that it might be good to have a bike.

A bike has other benefits, of course. It’s good exercise. It doesn’t burn gas. Bought from Walmart or Target, it costs less than six cab rides. And I can leave it to Goodwill, or a Boys & Girls Club, or some other association, so someone can benefit from a nearly-new bike.

Enamoured with this idea, I shopped around. Sure enough, a simple, one-speed road bike was $99 on Walmart.com. I’d made up my mind: In a few weeks, I’d buy it, and ship it to a friend’s in Austin. I didn’t want it lying around in her house for too long, after all.

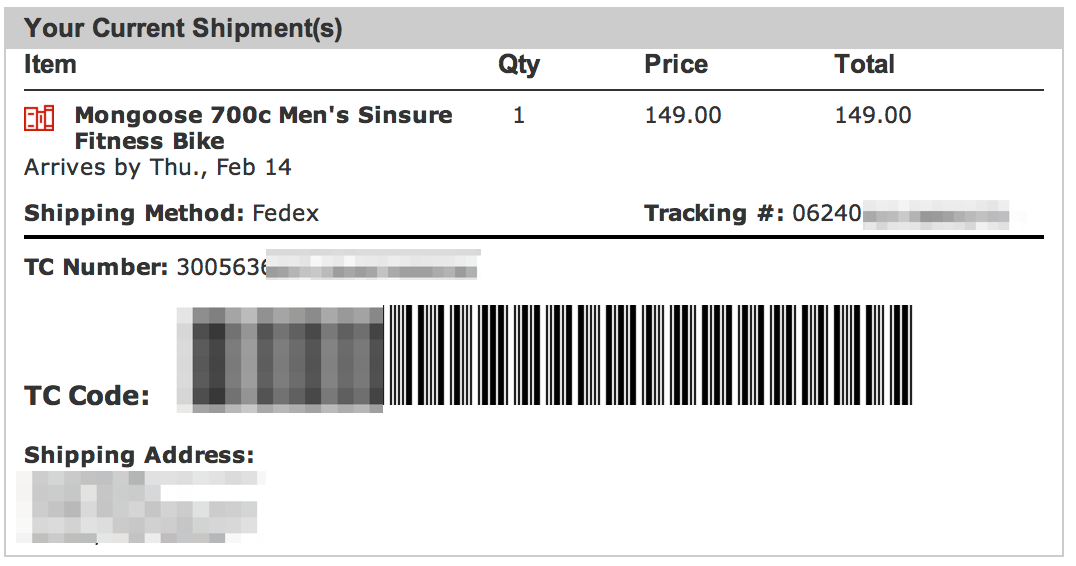

When the middle of February rolled around, I went back to Walmart, only to find the price had gone up by $50. Undaunted, I bought the bike, and shipped it. I knew I’d have to do some assembly, but this seemed a small price to pay.

Shortly after I’d drop-shipped the bike, I found out that another friend (who’s busy changing the world) wouldn’t be able to make it, and her partner had a spare room in downtown Austin at La Quinta, just a few blocks from the conference. The long journey I’d feared would, for the most part, not happen. I’d be walking distance from things for much of the conference.

(If you came here for Lean Analytics stuff, bear with me—we’re getting there.)

A few days later, I flew from Montreal to Newark, where, apparently, they don’t know how to deal with snow. As a result, I arrived in Austin late, missing a dinner and a Big Data meetup. I took a taxi to the Holiday Inn Express far North of the city, and crashed, surrounded by boxes of books rushed from the printer to my hotel.

I woke early the next morning, and my Austin friend came to pick me, my luggage, and my boxes of hot-off-the-press books up.

We drove to a Walmart near her house for supplies. This was my first real warning. In front of me were rows and rows of pre-assembled bikes, hanging from the rafters in an array of styles.

Had I known I’d be here to buy a helmet and other things, I could simply have bought a bike that was ready to ride, and skipped the assembly, and not needed tools. Lesson learned.

Eventually we found our way to the bike supplies themselves. These were, to say the least, lacking. Most of them featured a licensed cartoon character of some sort, and few of the helmets fit my head.

The locks were witheringly frail, but I rationalized that a cheap bike was unlikely to get stolen. In the end, I left with a helmet, lights, a bike lock, and some basic tools. I was also $97.22 lighter.

Then we went to her place, and I spent an hour or so assembling the bike. This was a sweaty, uncertain process. Fortunately, I’d found the right tools, but even then it was tricky in places, particularly in getting the brakes properly aligned. After an hour, I stood back to review my handiwork.

Now, if you look closely at that picture, you’ll realize something that had only just occurred to me. Those tires aren’t inflated. Lesson learned. Having not thought this through, I now needed to find a bike pump. My friend drove me to my second hotel, downtown—already, I was missing the opening sessions of the Lean Startup workshop at the Hilton—and fortunately the parking staff had an air compressor on hand.

I thanked her for her help, changed, and biked off towards registration. I flew down a surprising number of hills on my way towards the river, regretting with each street I crossed the potential energy I was bleeding off, and the kinetic energy I’d have to give back on the return trip.

I need to pause, at this point, to say one important thing:

Having a bike at SXSW is fantastic.

The feeling of caroming around corners, hair in the wind, street rolling by, is wonderful. It’s exhilarating. I have no regrets. But if that sounds like foreshadowing, well, it is.

Badge and swag retrieved from the well-oiled machine that is SXSW, I hopped back on the bike—which handled fairly well—and pedalled a few blocks to the Lean Startup event. I spent some time there, and left to meet Blake at a party. I walked out of the Hilton with a spring in my step, ready to board my trusty steel steed and head off to the event …

And stopped. My front tire had a flat.

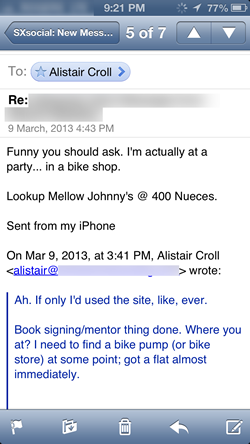

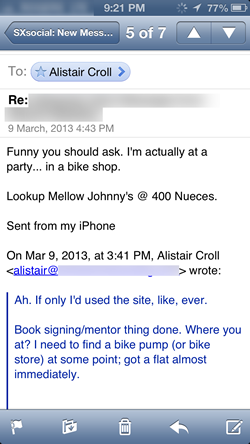

I texted Blake to tell him I couldn’t come to the party, because I had to fix my tire. Then this happened.

Apparently, SXSW provides. In this case, it provides a Chevy Volt party next to a bike repair shop.

Okay, if you’re here for the Lean Analytics stuff, this is where it will make sense. Because as I walked the ten blocks to Mellow Johnny’s, I had time to reflect. Normally, all of this would have made me furious—paying too much, realizing I’d made dumb mistakes, having a flat. But I was kind of enjoying it. My whole frame of mind had shifted from “I need a bike” to “I am running an experiment.”

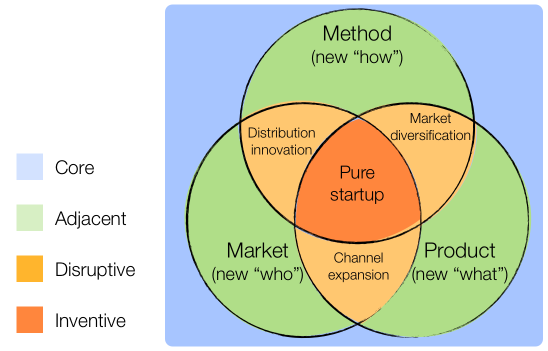

As I’d been preparing for the trip, I’d thought to myself, “maybe someone should start a business for travellers who want to keep in shape.” For all the reasons I’ve mentioned, having a bike in a city is great. And giving it to goodwill—possibly with a tax receipt in the process—might make it a viable business model. But I hadn’t got out of the building.

Now here I was, decidedly out of the building, walking a dilapidated bike down a dusty street in a city I didn’t know. And I was loving it. I’d learned at least ten things about this hypothetical bike-in-a-city business in less than a day, and all of them were crucial to the business. Never mind that I had no intention of setting up such a business. Simply viewing it as an experiment turned every mishap into a triumph.

It’s hard to explain the Zen-like calm that had overcome me. But I didn’t have time to muse any more—I’d arrived at my destination.

Outside Mellow Johnny’s, it was SXSW as usual—dozens of people, all staring at their phones, oblivious to the other people they’d travelled hundreds of miles to see. I walked my bike into the store and introduced myself to one of their staff.

His first reaction was a compliment—he liked the bike. It seems the designers at Walmart had conceived a vehicle that, on initial inspection, looked solid and well designed. I explained the provenance of said bike, and the history, and he quickly changed his mind.

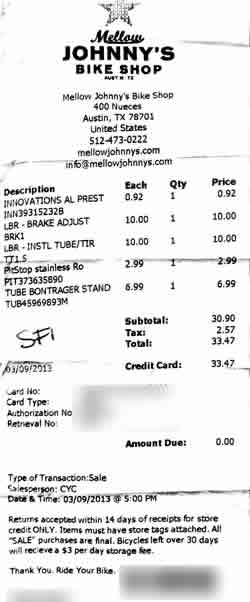

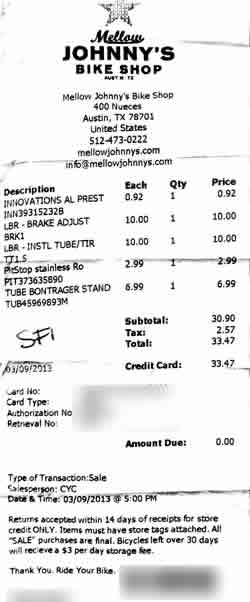

He agreed to repair the tire, and check the brakes for me. There was a small tear in the tube, so he’d replaced it. As it turns out, the tires on the bike weren’t standard, requiring not only a new tube but also an adapter for the valve. Lesson learned.

$30 poorer, but delighted with the staff, service, and coffee at Mellow Johnny’s, I headed off. I was only slightly worried by his parting words: “I fixed those brakes as best I could, but I wouldn’t go down any hills if I were you.” After a few more events that evening—abetted by my ability to flit from venue to venue quickly—I returned to my hotel, locked up the bike, and went to sleep.

The following morning, I found a relatively unsullied coffee shop with good Wifi, did some work, grabbed a great brunch at an Exact Target party, and went to see friends at the Canadian tech pavillion. By now, I’d noticed that my bike had some wear and tear. The seat, for example, had started to split from the moisture and exposure of the overnight rain. Lesson learned.

Then I returned to my hotel for a board call, and headed back out to meet my friend and past co-author Sean. We decided not to wait in the line for Girl Talk, and instead headed to the Driskill.

Now, if you’d been out all night, you might be upset when you walk out of the bar and find …

… your back tire now has a flat.

Not me. My Zen-like attitude was unassailable. Joy! More data points for my test case! More lessons learned!

Sean clearly thought I was mad. But I was reminded of something Dave McClure said at Startupfest last year: The only thing worse than bad feedback is no feedback at all. Here I was, walking back to La Quinta with a flat tire once again, absolutely swimming in negative feedback!

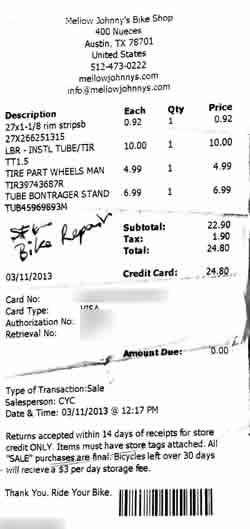

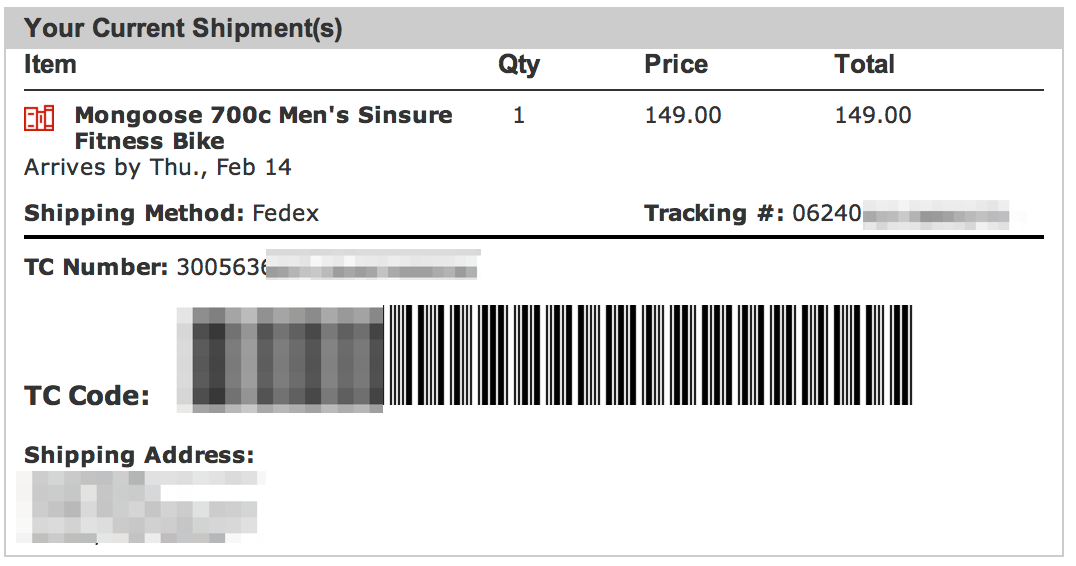

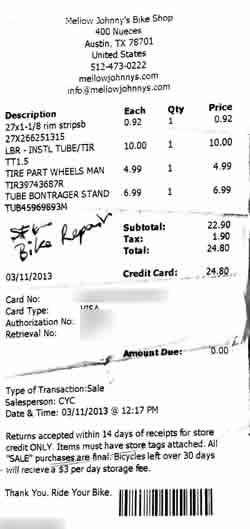

The following morning I had to pack my bags and leave them at the downtown hotel. My respite from the long ride was over; I’d have to rely on my bike to get to and from the original, distant hotel. I walked back to Mellow Johnny’s and had the bike repaired a second time.

Another $24.80 spent. I did learn, however, that renting a bike from Mellow Johnny’s would have cost me $25 a day. I took a moment to delight in this nugget of competitive pricing data, and another lesson learned.

I biked off for a quick chat with some of the folks from Soundcloud, then made my way across the bridge to a video interview I had scheduled with the folks at Software Advice (which I’ll post here sometime soon.)

Did I mention that having a bike in Austin is amazing?

The wind across the river, and the spring sun, were fantastic. I climbed a short hill, and turned down a smaller road towards the studio. And then I noticed that the wheels were making a strange noise.

Flat number three.

Again, at this point, I’d normally have thrown the bike off an embankment. But this was a lesson, to be consumed, considered, and shared, dear reader, with you. I walked my bike the remaining distance to the studio, and did the interview with Ashley Verrill, who handled a rather sweaty guest with poise and aplomb. Shortly afterwards, I was scheduled to speak with a bunch of librarians about Big Data, and they’d kindly offered to pick me up. So I asked them if they had room for a bike.

We squeezed the bike, and five passengers, into an SUV and crawled the few miles to the next venue. It was during this drive, shoehorned between seats and spokes, that I learned I was far from the first to consider getting bikes in each city I visited. No, David Byrne has been doing this a long time, and has even written a book—the Bicycle Diaries—about it.

The hypothetical-startup-founder in me celebrated: I’d unearthed a competitor! Another lesson learned.

When we finally reached our destination, my Austin native—who’d patiently waited while I assembled the bike in the first place—was there. She told me of a friend had recently lost everything, even her car, and badly needed a way to get around. So I gave her the bike, with $20 to fix the third flat.

Things have a funny way of working themselves out.

I’d spent $314.49 on my bike experiment. The rest of the conference was uneventful by comparison. There were some great parties, and the aforementioned RVIP. Reggie Watts helped us skip a line. And the workshop went really well, giving me insight into how social media marketers and agencies think about metrics—and into why vanity metrics won’t die. But that’s for another day.

I learned a lot from the experience. It reminded me just how vital it is to get out of the office and try something yourself. And it demonstrated what a difference it makes when you think of your experiences as experiments. They cease to be disappointments and become learnings. Even if you’re not starting a company right now, pick a crazy, hare-brained idea and see if it works. It’s refreshing.

Ultimately, when you’re trying something new, you’re not defined by your idea, your product, your plans, or your services. Rather, you’re defined by what they’ve taught you. This is true for founders, but it’s also true for humans. It’s a much more Zen way to look at your life.

And that’s why, for me, the best thing about SXSW 2013 was a shitty bike.

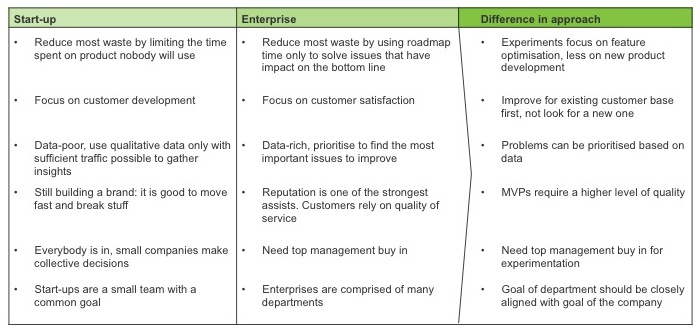

Recently, Bayram Annakov of Appintheair wrote to us about how he’d used analytics and Lean approaches to improve his user onboarding, with some pretty dramatic results. He was kind enough to outline them here for all of us.

Recently, Bayram Annakov of Appintheair wrote to us about how he’d used analytics and Lean approaches to improve his user onboarding, with some pretty dramatic results. He was kind enough to outline them here for all of us.